It's easy to forget that as recently as the mid- 1970’s, people who exercised regularly, ate whole-wheat bread, and preferred bottled water to mixed drinks were considered "health nuts."

There are a lot of health nuts around these days. It's now commonplace, when visiting a business office to find a little group of smokers huddled outside the door, furtively puffing away. One can enjoy an evening of party hopping and never be offered anything stronger than lite beer. It's possible in some circles, to go for weeks without seeing a single chunk of red meat or a slice of white bread.

This growing trend toward self-care is not limited to the well. Those with health problems are also taking a greater degree of responsibility. Health consumers in increasing numbers are requesting more second opinions, demanding clear explanations, and reserving final decisions about diagnosis and treatment for themselves. They are consulting alternative practitioners, with or without the support of their regular health professionals. In many cases they are choosing to deal with their problems without professional assistance of any kind.

Such changes have already started to affect the use of professional health care. People who practice self-care use fewer professional services. A University of Chicago study found that self-caring persons spent 26 percent less on hospital bills and 19 percent less on physicians' services.'

A Health Care Revolution. This trend toward increasing self-responsibility in health shows every sign of gaining momentum. The self-care health market has become one of the fastest growing segments of our economy. Americans by the millions are investing in stationary bicycles, weight-training machines, and other exercise equipment. At the same time we are turning away from liquor, cigarettes, and high-fat foods. Firms which provide self-care goods and services are, on the whole doing extremely well, while products which have fallen victim to the new health consciousness are being forced to take desperate measures. The best-selling brand of liquor in the U. S., Bacardi rum. now proudly announces that a rum and orange juice contains less alcohol than a five ounce glass of white wine. Hiram Walker recently introduced a line of low-alcohol Haagen-Dazs cream drinks. Seagram is testing a no-alcohol wine.

The tobacco industry has been hit hardest of all. Since the first Surgeon General's report in 1964, per capita smoking has plummeted 39 percent. The proportion of Americans who smoke is at its lowest point in decades—and still falling. Even the president of the Reynolds Tobacco Company now admits that in the long run—it may take a century or two—the smoking industry will probably die out altogether2.

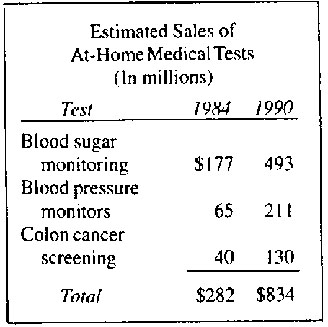

We are also buying more self-care books: From 1977 to 1981, estimated sales of health related books increased by over 1100 percent. We are reading more health magazines: From 1970 to 1980, sales of special interest health magazines more than doubled3. We are buying more at-home diagnostic tests: From 1984 to 1990 the sales of the top three at-home diagnostic tests are expected to grow by nearly 300 percents4.

The New Hearth Care System. One could go on and on citing similar figures, but it might be more interesting to ask exactly what they mean. Do they reflect actual changes in the way we think and act about health? I believe they do. When medical historians look back at the last quarter of the 20th century, I believe they will view it as a transition period from an old health care system built around the doctor, the hospital, and the clinic to a new health care system built around the individual, the family, and the home.

Structuring a health care system around the individual might seem like a contradiction in terms. Isn't health care what doctors and nurses do? Under the old system, yes, but not under the new model. If health care is the process of keeping oneself—or someone else—as healthy as possible and managing health problems when they occur, then it's clear that the great majority of health care is now and has always been self-care.

I've found it useful to think of health care as a stool with four legs: tools, skills, information, and support. Let's suppose you have a sliver in your foot. Many of us, provided with a good pair of tweezers, a good light, and a clean needle, could probably take it out. We might have trouble, however, if we lacked light, tweezer, or needle (tools), the required hand-eye coordination (skill), if we did not understand the proper way to go about it (information) or if we had been told that it was simply not appropriate for someone not a health professional to do such a thing (support).

In the old, physician-cantered health care system, the assumption was that the medical domain was limited to physicians and other health professionals. Such tools such as scalpels, operating suites, and electrocardiographs, such skills as taking a throat culture, or performing a physical exam were for doctors only. Information was to be found in medical journals and textbooks and at medical meetings. Support services were provided by hospitals, laboratories, nurses, and doctors' office staff.

The Near System. But if we employ the assumptions of the new, self-care-centered health care system, we see things a little differently: Tools include both devices to promote wellness—running shoes, exercise bikes, relaxation tapes, workout videotapes, etc.—and those used to detect, manage, and treat disease—blood pressure cuffs, otoscopes, prescription and over-the-counter drugs, and a growing number of at-home laboratory tests to detect such things as pregnancy, blood in the stool, or time of ovulation. Medical skills now passing into the lay domain include taking a throat culture, taking a blood pressure, performing physical exam, doing a screening test for colon cancer, and choosing the most appropriate OTC drugs or alternative remedies.

Information includes knowledge of preventive measures (nutrition, exercise, stress reduction), disease management (arthritis, cancer, high blood pressure), and medical consumerism (making decisions about surgery, drugs, and medical tests, and checking up on your own medical care). Support consists of educational programs, self-help groups, and medical consumer organizations—as well as health workers who encourage and support self-care. In the case of home health care it might also include respite and support services for those who care for a family member with a chronic illness.

REFERENCES

1. John Fiorello, Editor, Helping Ourselves to Health: The Self-Care and Personal Health Enhancement Market in the U.S. New York, 1983, The Health Strategy Group, 325 Spring St., New York NY 10013, p.67.

2. Sherman, Stratford P., "America's New Abstinence," Fortune, March 18, 1985, pp. 20— 23.

3. Fiorello, p.37.

4. Peter J. Allen, Editor, The Self-Care Market, Find/SVP, The Information Clearinghouse, Inc. 500 Fifth Ave., New York NY 10110, p.v.